The best place to do business in the United States is Texas, followed by No. 2 Florida and, in a tie, No. 3 North Carolina and South Carolina, according to Chief Executive’s 2018 “Best and Worst States for Business.” CEOs ranked Indiana No. 5, rounding out the top five states.

The worst place is No. 50 California, bested only slightly by No. 49 New York, No. 48 Illinois, No. 47 New Jersey, No. 46 Connecticut and No. 45 Massachusetts.

Seem familiar? That’s because those are the exact same positions each of these states has occupied in each of the last four years in our annual poll of CEOs about business climates.

Meanwhile, there are fast and furious moves up and down by states in the middle. This year, Rhode Island rocketed up 10 spots to No. 32, while Michigan gained nine spots, up to No. 27. Nebraska fell six to No. 26, and Idaho plummeted by 10 to No. 28.

What explains the dynamism in CEO opinion of states in the middle while their impressions dictate complete stasis in the rankings at the top and bottom? Both realities and perceptions, say CEOs, state and local officials and economic development consultants.

“Generally those performing best and worst stay there because the states don’t see significant leadership changes,” says Larry Gigerich, managing director of Ginovus, an economic development consultancy in Fishers, Indiana. “They have a philosophy about how to approach the business climate and economic development. There’s more opportunity in the middle states for a change of leadership because those places tend to flip more philosophically, between parties or within parties.”

The top states recognize how truly important it is to maintain the business-friendly cultures that helped them grow dynamically even during the slow-go years following the Great Recession.

For example, “The fact that Indiana is generally a state ‘open for business’ is kind of accepted,” says Parker Beauchamp, CEO of INGUARD, an insurance and risk management firm of about 50 people headquartered in Wabash, Indiana. “It’s been good enough for long enough that people just kind of know there’s no shenanigans, no running hot and cold. It’s a very solid, all-around state.”

Texas has held the No. 1 spot for each of the 14 years since the inception of the Chief Executive survey.

“Texas has no corporate or personal state tax,” enthuses Bill Hall, CEO of Ultravision International, a Dallas-based LED lighting manufacturer. “And Texas gives us very highly skilled workers because of the number of great colleges we have.”

But, Avis-like, Florida and the Carolinas keep trying to knock Texas off the pinnacle.

Florida “is a very good place to do business, with relatively low regulations and relatively low cost of labor, a good university system and low cost of living with no income taxes,” says Jeff Vinik, the most prominent real estate investor in the Tampa Bay area.

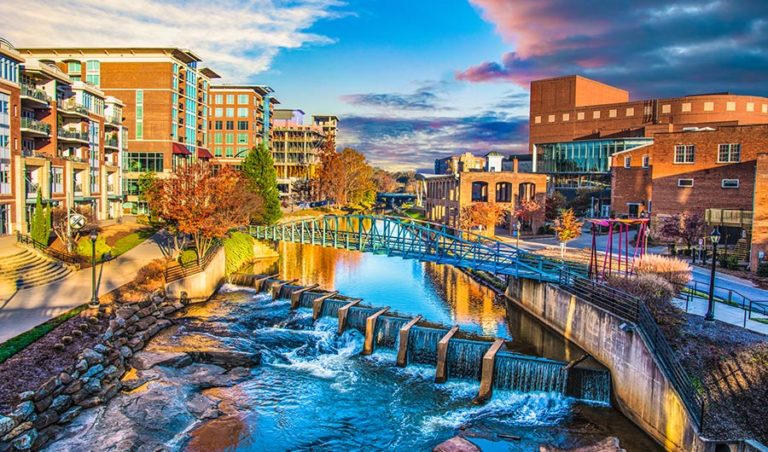

Michael McGuire says, “North Carolina has it right—it has a nice environment and climate and is business friendly, and while it doesn’t have a zero tax rate, property taxes are reasonable and so is the cost of living.” McGuire, CEO of Grant Thornton, adds, “Plus Charlotte and the Research Triangle are there.”

Meanwhile, the high-tax, high-cost environments created by the bottom states also tend to be self-reinforcing. Mostly, those places are kept afloat economically by legacy advantages such as strong education and healthcare systems, as well as by the fact that in-demand, digitally skilled millennials enjoy living in their cities.

But states like Massachusetts risk eroding even those advantages as the cost of living skyrockets in big cities and traffic and other annoyances mount. “There are so many businesses and so many people that it’s inflated the cost of everything,” complains Travis York, head of GYK Antler, a mid-market ad agency with offices in Massachusetts. “That’s made it hyper-competitive and, frankly, hard to get around.”

The situations of bottom feeders could get worse before they get better, in part because of a particular effect of federal tax reform on high-tax states—like the basement dwellers. “The exit numbers of companies and owners are going to be higher,” McGuire says, “because people won’t be able to deduct as much in property and income taxes. They’re being taxed into oblivion.” Also, the coasts are losing some of their perceived edge in talent and lifestyle amid sharply higher costs of living—and facing steadily increasing digital capabilities in the heartland.

“It’s getting to the point now where if you’re a digital marketing specialist, you can move to Nashville or Omaha and have three or four opportunities,” says David Hall, vice president for investments at Revolution LLC, a Washington, D.C.-based seed fund. “Before it was so scattered. You’re seeing the density of the tech and startup ecosystem build on itself and create great network effects within a region.”

Great talent in less expensive locales? That’s good news for business—and great news for the nation.