30 Years Ago, Mill Workers Fled South Carolina in Droves. Now, Its Startup Scene Is Making a Remarkable Transformation

South Carolina makes its three-city debut on the Surge Cities list this year, with hospitality, tech, and advanced manufacturing on the rise.

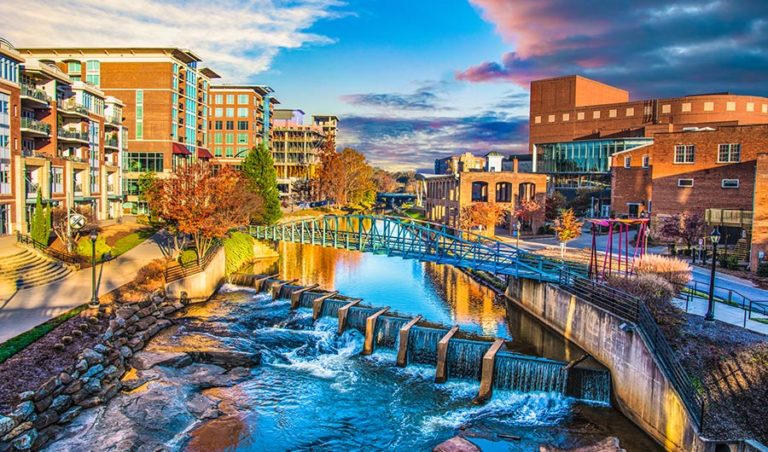

When Scott Millwood was growing up and going to college near Greenville, South Carolina, he says, “I didn’t see it as a place where I’d want to live.” With the textile industry moving its mills to Asia, “the city faced a really tough transition.” Millwood remembers the grand old Poinsett Hotel, erected in 1925, sitting vacant downtown. “There were no windows, and homeless people were burning trash-can fires in the fourth-floor ballroom.” Today, Scott is the chair of Next, a networking and mentoring organization for Greenville entrepreneurs, and the founder of an A.I.-powered digital-assistant startup called Yesflow. It’s the second successful tech company he’s started in the area. (Customer Effective, his first, was a five-time Inc. 5000 honoree that eventually sold to Hitachi.) As for the Poinsett, it, like the rest of downtown Greenville, has been handsomely restored and is thriving. It’s a Westin now. Over the past three decades, Greenville has completed a remarkable transformation.

Today, it debuts on the Surge Cities list at No. 33–one of three South Carolina cities, including Charleston and Columbia, to appear on the list for the first time. Each has drawn on unique strengths to build its startup scene, but all three also benefit from one another’s success. Greenville’s turnaround began 25 years ago, explains Chamber of Commerce president Carlos Phillips, when city leaders began aggressively recruiting manufacturers to tap into the city’s underemployed workforce and tax incentives. They succeeded in landing factories from both BMW and Michelin. “That got us out of the old economy and into the new assembly economy,” he says. But then, when an early Greenville-based tech company called Datastream was acquired in 2003 for $200 million, “people woke up and said there’s a new revolution underway. We need to be a part of it.”

Today, Greenville has the sixth-highest rate of business creation in the nation, and much of its startup ecosystem centers on business-to-business software companies. Some of the more exciting ones–Netalytics, ChartSpan, Kiyatec–make applications for medical use. Clemson University and several smaller area colleges turn out a steady stream of talent, who now want to stick around, and the lifestyle afforded by the city’s location near the Blue Ridge Mountains attracts outsiders. Enviable physical assets are also part of the draw in Charleston–a three-hour drive southeast from Greenville on Interstate 26. The church-spire-dotted Holy City (No. 7 on this year’s Surge Cities list) has long been a tourist destination, thanks to its many beaches and waterways, graceful old buildings, and deep history. In recent decades, though, a new generation of culinary talent has transformed the city’s Old South hospitality into a platform for creativity that has extended from the city’s world-renowned restaurants into new packaged-goods brands such as Cannonborough Craft Soda and the New Primal Beef Jerky.

In the same time frame, the number of tech startups also has risen in Charleston, thanks in large part to the alumni of several early successes such as Blackbaud (a now-public maker of software for nonprofits), Benefitfocus (also public; HR software), and Automated Trading Desk (acquired by Citigroup for $680 million). “The network of talent that came to town to work for those companies spun out their own companies and created the tech scene,” says Patrick Bryant, founder of digital developer Code/+/Trust and co-founder of the Harbor Entrepreneur Center co-working space. Bryant notes that many Charleston startups support industries that have long powered the city’s economy: the military, hospitality, a thriving port, and advanced manufacturing (the area houses Boeing, Volvo, and Mercedes plants). Almost exactly halfway between Charleston and Greenville on the I-26 corridor, Columbia (this year’s No. 42 city) is the state capital and home to the University of South Carolina–which gives it a disproportionate amount of intellectual firepower for a city with a population of 150,000. Although its entrepreneurial scene is a few steps behind those of its Surge Cities brethren in South Carolina, that’s beginning to change.

Laura Boccanfuso, the founder of Vän Robotics, left a position at Yale University to start her company in Columbia, where she had earned her PhD at USC. She chose the city for lifestyle reasons–it’s a nice place to raise a family–but worried that it would be hard to attract the right talent to a town where no one else worked in her niche. She’s found it more than possible. One recent hire came from Johns Hopkins. To Boccanfuso, Columbia’s rise as a hub for entrepreneurship reflects a broadening perspective in the region. “The cities are watching each other,” she says, “and trying to tap into each other’s momentum. Not only are people in Columbia reaching out to people in Charleston and Greenville, but people in those cities are also starting to reach out to us.” A state-chartered nonprofit headquartered in Columbia, the South Carolina Research Authority exists precisely to build that kind of statewide cooperation by offering early-stage funding and mentorship to entrepreneurs in all three cities. “If we didn’t have SCRA as a statewide resource, we wouldn’t be putting Greenville, Charleston, and Columbia on the map,” says Caroline Crowder, program director of the USC Columbia Technology Incubator. Meanwhile, VCs from Atlanta and the Northeast are prowling for deals–and in the case of Atlanta’s BIP Capital, even opening offices–in the state.

As more established and more expensive power centers on both coasts see more people opt out, the Palmetto State stands to benefit from a southward momentum. This year, 40 percent of our Surge Cities are below the Mason-Dixon Line. As Patrick Bryant says of Charleston, “Who wouldn’t want to move to a place where they might spend a vacation?”